|

Jones,

one of the relatively few professional jugglers to hold office, took

over an organization bursting at the seams and applied his business

acumen to its future. His was an investment philosophy of spending money

to make money, and he pushed the IJA into a more formal, modern,

professional direction. Today, the change seems to have been inevitable, but debate over IJA policy and goals continues.

On

the one hand were those who remembered the old conventions of 20 and 30

people. It was hard to reconcile the informal intimacy of the old IJA

with the new directions it was taking. Allied with these older veterans

were those who believed the

Other

members saw bigger as better. Tougher planning meant better results, and

more money meant better plans and more fun.

These

two sides of the same coin were arguing each other's reflection: 1)

Juggling is such a pure delight, it will spread by its own force of

rightness. 2) Juggling is such a pure delight, let's package it and

deliver it to the home of every child in the world.

While

the controversy over principles was as great as the controversy over

personalities 20 years before, juggling and the IJA were far too big to

be damaged. Instead, the dissension broadened the scope of juggling and

the forces settled into a truce. Bigness was inevitable. That was cruel

irony for those who sought to stifle it. The very people who wanted a

sleeping bag and rice ambience in the IJA swelled the organization into

bigness. And those who sought a more formal structure had to accommodate

the more relaxed views of others.

In

the end, we find ourselves pretty happily situated between late night

Club Renegade scenes and nationally covered Las Vegas-style

championships. The IJA may have become big-time, but, as Gene Jones

pointed out, you'd have to have a pretty jaundiced eye to call the IJA |

|

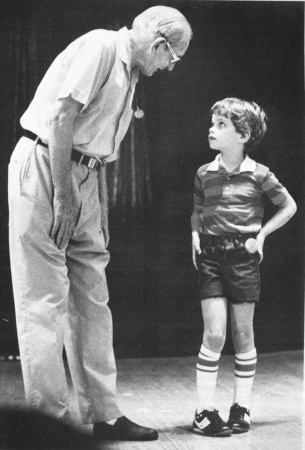

Old and new blend to form a rich tradition of IJA history. Bobby May and Anthony Gatto meet at the 1981 convention in Cleveland, Ohio. Juggler's World photo. |