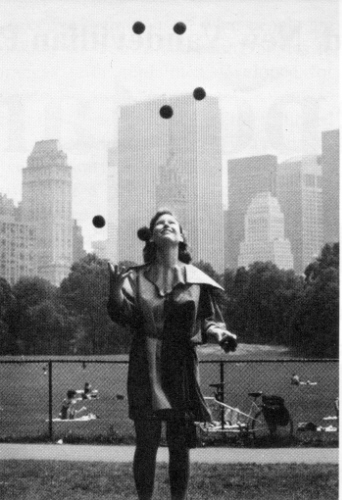

Cindy Marvell, photo by Cindy Heywood |

Page 21 Fall 1989

|

Then

I really enjoyed my Sunday afternoons with the Falling Debris Juggling

Club in Central Park when I was about 14 to 16. I named it that,

Falling Debris Juggling Club. My father used to come along with me,

and actually got inspired by me to learn clubs and four balls. My aunt

and sister, Elinor, also came. Elinor was at the Baltimore convention.

She and her friend Linda did Club Renegade where they passed clubs and

sang.

Once

I decided in high school I wanted to be a professional juggler, I'd

get depressed because I didn't see how it would work. I pursued it,

though. I did some performances, like for the Carnegie Hall Serenade

Festival my senior year, and I performed for Project Sunshine, a

volunteer group at hospitals and nursing homes. Then I went to the

Antic Arts program with Berkey, Garbo and Moschen at SUNYPurchase

when I was 15 or 16. It was right before the Purchase convention, and

turned out to be a great thing. That workshop changed me a lot, there

was a lot of very creative stretching, creating things more for the

sake of creating them than finishing them. Before I went to Antic

Arts, mine were more one-dimensional routines, but they gave us a

healthy guilt about just juggling. JW:

Sort of an anti-tech, pro-arts attitude, huh? You seem to have

found the best of both worlds in your routine now.

CM:

I've rejected some of the anti-tech thought recently, but I felt

guilty about doing just technical juggling for a long time after that

summer. They kept getting us to think of juggling as art to be used

for other goals. But technical juggling isn't mindless. You can create

through your technique to go beyond technique. At conventions you see

a lot of mindless juggling going on, and I can understand the reaction

against that, but isn't right to just throw technique out the window.

You use technique to get somewhere. Like going deeper within and

coming out the other side.

Even

when I do comedy it revolves around the technique itself. My comedy is

juggling with a patter, a lot of visual puns. I did a routine that

imitated different rides at a theme park, like the scrambler and

bumper cars. I have a four club routine that imitates famous places of

the world like Niagara Falls, Grand Canyon and the Eiffel Tower. I

also do torches and diabolo in street show, a unicycle, devil stick

occasionally, and I love walking on stilts!

I

used to think it was creative to use different objects, but my ideas

have changed lot in past year or two. On one hand you can say it's

unoriginal to do balls, clubs and rings because that's what people

have always done. But there is something essential about those props,

that's why they've held up over the years. I used to think juggling

different objects was a sign of originality, but now I think it isn't

unless you manipulate them differently. The originality is more the

manipulation than in finding a tennis shoe or Webster dictionary to

juggle. The important thing in juggling is not the objects but the

path that they're marking. JW:

You sound pretty versatile --

comedy street shows, the musical routine for the championships, and

when we saw you in Atlanta at Groundhog's Day, you were juggling to

classical poetry! How did you arrive at the poetry routines?

CM:

My poetry routines mostly came from Oberlin. The first one was the

opening chorus to Henry V. I performed it with three clubs at the Las

Vegas convention in the Public Show. At Oberlin I made up two or three

more routines, then senior year I got some ideas for other poems. It

occurred to me that all these poems had certain things in common with

each other and the way I was thinking about juggling. My winter term

project was "Magic In the Web," an hourlong show with just

poetry routines. I don't have an hour's worth of anything else!

Most

of the poems were from the Romantic period, poems by Shelly, Keats and

Wallace Stevens. They have a definite form and rhyme scheme that makes

them fit well with juggling's regular beat. Part of what I'm doing is

to get the rhythm as well as the meaning across. Some of the tricks

are meant to go with the rhythm and others are images of the words.

The poems are all about things elusive, things that fade away, like time and beauty. And that's like juggling because the pattern fades. Your juggling doesn't exist unless you're doing it. It's so fragile. Juggling is gone the instant you stop. That's one of the things that helps make juggling artistic, it forces you to be spontaneous, to come up with new ideas. It forces you to think about what you're doing because it doesn't last. It's completely dependent on you.

Juggling

or dance has to be constantly created, it never becomes distant from

you. It can't exist without you.

JW:

The big question for champions

is always, "Now that you've won the big one, what are you going

to do now?"

CM:

Ultimately I would like to do an Oberlin-type show with poetry,

but it would be a big theatrical undertaking. I'm also enjoying doing

my comedy show. I'd like to work with a small circus at some point,

and work in Europe some. I'm taking my IJA prize money to go to

Maastricht. JW:

Do you ever worry about whether

you can make it as a professional juggler?

CM:

I worry about my professional direction all the time. It caused me a

lot of anxiety in college. Most people are anxious because they don't

know what they want to do. I knew what I wanted to do, but was more

anxious because everyone told me I couldn't do that for a living! I've

gotten good enough at the street/comedy show to do it, but it isn't my

strongest thing. The music and poetry are my strength, but there's

almost nowhere to do them.

I

guess it's frustrating to not be able to do what I do best, but it's

common. A lot of artistes feel that way. For artistes, pushing your

own limits doesn't fit into established categories.

But

I haven't been doing it full-time very long. After all, I just

graduated from college last year. So you never know what may happen! |

Cindy Marvell, photo by Cindy Heywood |