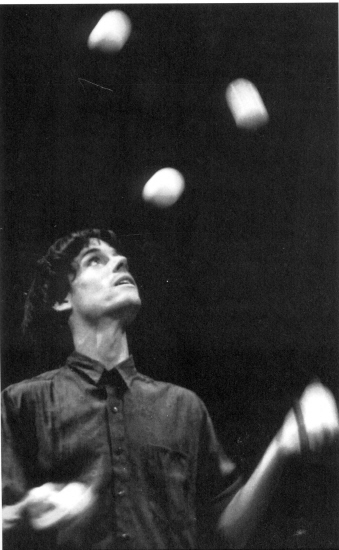

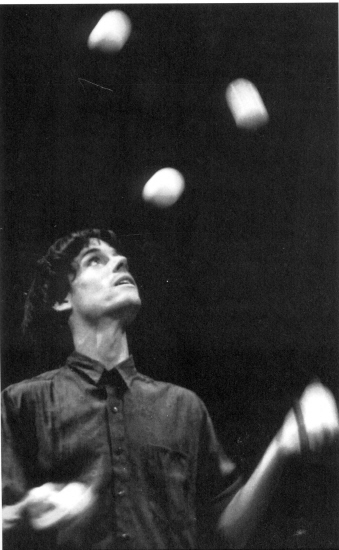

Peter Davison in Cascade des Etoiles public show (photo Bill Giduz) |

Page 16 Summer, 1994

|

Thoughts

on Thoughts While Practicing BY

PETER DAVISON

For

jugglers, it's a perennial question: What is the most effective way

to go about

learning new tricks?

Certainly

there are times when we are not so concerned with learning a trick,

for example when we are juggling with other people, playing,

relaxing or inventing moves. What I'm thinking about here is the

process of practicing alone in order to learn technique, and the

following are some ideas that I have found to be useful in my own

work.

First

of all, let's assume that we have figured out exactly what the

physical necessities of a new trick will be (the pattern, body

positions, rotations and timing). Now we become involved in trying

to get our body / mind to learn it, by developing reflexes that

operate faster than our conscious thoughts.

Concentration As

we begin to practice, we have the idea that we must concentrate. But

what is concentration? Ultimately, concentration means placing our

full attention on each attempt at a trick, doing and experiencing

totally, without distraction. To the extent that we can do this, we

allow our body/mind to learn most efficiently.

But

this way of working is easier said than done, because of the variety

of distractions that can affect us. I have noticed that the most

powerful distractions are often in the mind, in the form of thoughts

which stem from the desire to achieve a goal. These thoughts include

large or small fantasies about what will happen after a trick has

been learned. In my case, I often see myself performing this new

trick, and I envision the venue, the cheering audience, the new

respect I'll gain. Yes,

How

can we reduce these distracting thoughts? How can we develop a clear

mind that can see and feel what is happening now so we can learn

most efficiently? Perhaps

we can employ a Zen-like paradox: By being unattached to

Of

course, the idea of success fuels our desire to practice in the

first place. But what if we can leave the idea of success on the

doorstep, and enter into practice without "needing to get

better?"

We

know that by practicing with concentration we will make progress,

even without a particular goal in mind. So now, our attitude can be

that this practice session will be our life at this time, and we

will experience it fully in its own right. Any future success can be

seen as a by-product of this experience of practicing. Our goals

will be reached because of. our choices about what we will practice,

and now we engage in the process of learning with full presence of

mind and body.

For

most of us, though, it would be realistic to say that our goals will

remain with us, at some level, while practicing. But we can learn to

move them from the forefront of our consciousness while we practice,

and gain an increasingly clear view of what we are doing. Motivation As

we do this, another question comes up: Where does the motivation to

work come from when we reduce our conscious desire to reach a goal

during practice?

In

the past, I would practice only as work necessary to achieve a goal.

Now, my attitude is more that practicing is the goal. Ultimately,

why is throwing things in the air and trying to catch them a less

worthwhile experience than anything else? In fact, it can be very

interesting to experience our learning process - the various

attempts by our body / mind in trying to find the correct action,

not to mention often taken for granted effects such as gravity,

momentum and mass. Many things are happening at a subconscious

(hyper-conscious?) level, faster than we can realize in thoughts.

We

can observe and appreciate all of this, placing greater value on the

process of practicing itself. Simultaneously, we can place less

value on our images of future success. After all, they are just

images that have very little to do with what our experience actually

will be after we've learned the trick. Positive

Failure Traditionally,

there has been a view of practicing that includes good and bad, for

example, "I'm having a good practice," or "It's not

going well today." Particularly challenging are those times

when we are "worse" at a trick than we were yesterday. We

feel that it is only when we are increasing the number of throws

with a trick, or otherwise visibly succeeding, that we are making

progress.

Actually,

success and failures are both positive

aspects of the process. While we are dropping things on the

floor over and over, our body / mind is experimenting. It is

progressively searching for the correct action, the right feeling.

We can compare this

process to weight lifting, in which the difficult (stress) of

lifting stimulates strengthening of the muscles.

In

juggling practice, it is our failed attempts that are strengthening

our awareness. We need to accept difficulties, and then immerse

ourselves in them for a while, to learn effectively from them.

Later, as we begin to find the correct action, mistakes continue

to strengthen our abilities by introducing

"bad habits" to be overcome

and "saves" that have to be made, all of which

give us a more profound knowledge

of what we are doing.

Learning

Like A Child As

we are working through difficulties, there is a tendency to

intellectualize solulions. This involves describing a problem In

words, and then creating a similar description of a way to correct it.

For instance, "My left hand is throwing too high. I will

now throw lower with that hand." An intellectual approach

is necessary when we

are still in the phase of figuring out technical details and

aren't quite sure where

or when everything needs to go. But when working on something

that has been figured out, intellectual word descriptions can get in

the way of learning, because they will generally be incomplete. Often,

the "left hand throwing too high" is just a symptom of

several other actions that we may not be aware of.

So,

another way to approach making corrections is to get back to clearing

the mind. As we experience a problem, we can try to just see and feel

what is, without attaching a word description to it. We can try to

"remember" what happened in a failed or successful attempt

with the senses, in an all - encompassing feeling rather than an idea.

Really, all of the information that we need is in us before we start

to process it into a pat description, and we can work more directly by

using the information in that immediate state. This is how children

learn certain skills so quickly. They skip the stage of making up

intellectual descriptions of input, and act on input directly.

Again,

as jugglers we are often in the process of reasoning out the details

of a new trick and learning it physically at the same time. Therefore,

in my own work, I have found it necessary to "juggle" the

intellectual and experiential approaches to practicing, switching from

one to the other when appropriate.

Level

of Difficulty Another

standard thought pattern to be aware of is assigning a level of

difficulty to a trick. The natural tendency is to decide early on that

it is "really hard." Or, at the other extreme, to call it

"a piece of cake" in order to build confidence. In fact, any

particular judgment about how difficult a trick is will generally be

inaccurate, especially since the level of difficulty for us will be

constantly changing during the learning process. An opinion about how

difficult, or easy, we think a trick should be can directly affect the

clarity of our focus. So, rather than inventing a level of difficulty,

we can say that tricks are neither particularly hard or easy, they

simply are what they are at the moment.

This

brings us back to the central theme behind these ideas - to be fully

present in what is actually happening in our attempts. The most

effective way to practice is:

to just practice.

~O

Peter

Davison has

been juggling for more than 20 years. He is the 1982 IJA

Champion, and was a member of the trio Airjazz. with whom he

toured extensively for nine years. Currently he is pursuing

a solo career as a juggler and dancer, and will be

co-directing, with Michael Menes, the Progressive |

Peter Davison in Cascade des Etoiles public show (photo Bill Giduz) |