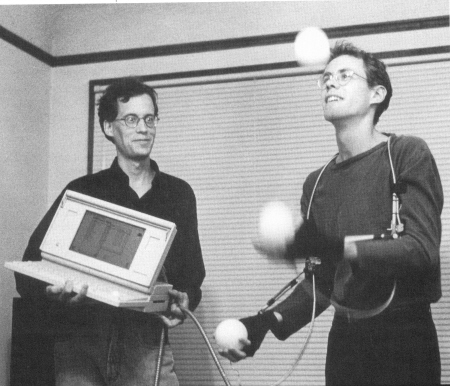

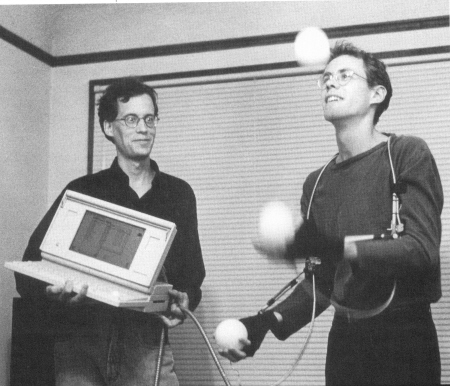

Collaborator Bret Battey and James Jay created the Juggling Jukebox. (Photo by Lincoln McNey) |

Page 26 Spring 1996

|

"Is

it real?" As

Last

fall James Jay and I arranged to conduct a real-time, online interview

over the Internet (using Unix's "talk" facility, for the

techno-savvy). This Performance

History JW:

How did you get into juggling originally? JJ:

I learned juggling as an undergraduate at Earlham College (Class of

'90) in Richmond, lnd. I suppose learning juggling in college isn't

that unusual, but I actually learned in a juggling class, for credit,

which is a bit odd.

JW:

What were you majoring in, and how did you decide to take the

juggling class? JJ:

I majored in English literature. Earlham is a very academically

conservative school, but for some reason they had a physical education

requirement. A student organized a juggling class as one of the

"Sport and Movement Studies" options.

JW:

How did the idea of the "Juggling Jukebox" first occur to

you? JJ:

After moving to Seattle in 1990, I was trying to think of a way for a

juggling act to work at Pike Place Market. The market is the place for

street performing in Seattle, but the spaces are very small, so a

traditional juggling act doesn't work. I had been thinking about what

would work in a confined space, and

JW:

What "robotic thing?" JJ:

A lot of young black men stand on the waterfront with music playing

from boom-boxes. They will stand with a cup out and do some robotics

when you put money in their cup. The more money, the longer the

performance. So there are some precursors that I owe part of the idea

too, but I have never seen

JW:

Had you done much performing before the Jukebox? JJ:

At the Pike Place Market Festival, I had a paid gig performing in

the Kid's Alley. That went alright, but it was pretty much like other

juggling acts. As I was exploring the idea of getting out and street

performing, I realized that the traditional street act didn't really

play well with my strengths. By nature, I'm somewhat reserved, so the

Juggling Jukebox (which is totally silent) worked well for me. It's

very focused, so I could practice the specific mime skills that I

needed. It concentrates on showing tricks, which is what most jugglers

work on but most acts squeeze in between the jokes. So I could use my

juggling

JW:

How did this evolve into the high-tech version? JJ:

After I had been performing the original (low-tech) Jukebox for a bit

over two years, I came across a grant offered by 911 Media Arts

(a Seattle-based center for the development of the artistic

application of broadcast, video and communication technologies). They,

along with a group called Northwest Cyberartists were putting on an

art and technology festival and conference called "Beyond Fast

Forward." I had another idea for a street performing stage JW:

What is the relationship between the high-tech Juggling Jukebox

and other hightech juggling acts such as the Karamazovs body suit

routine and Dan Menendez's bounce piano routine? JJ:

The Juggling Jukebox is unique in that it uses computer readings

of movement as well as hits. Every other high-tech juggling routine

uses a ball hitting a drum pad, keyboard key, or body trigger. The

high-tech Jukebox uses triggers on my palms, but also measures the

movement in my elbow. I see this as expanding the possibilities

significantly - instead of a 0 or 1, you're receiving a value between

0 and 255, so you can control pitch, volume, tempo, anything that's

not a simple on/off value. This permits a much richer set of

responses. |

Collaborator Bret Battey and James Jay created the Juggling Jukebox. (Photo by Lincoln McNey) |