|

Page 12 Winter 1989 - 90

|

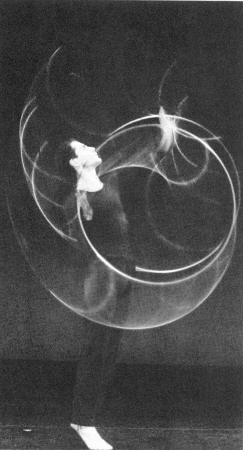

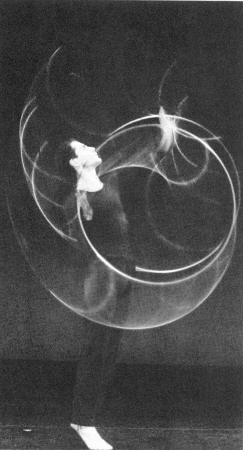

A

break-through followed, in the form of his wellknown work with

crystal balls, which seem to shimmer and

Then

came the stick piece, with a feeling opposite to the crystal balls.

He associated the metal rods with the use

Moschen

doesn't expect or want the audience to be overtly conscious of such

specific factors behind his work, but just "the fascination and

the almost hypnotic quality, the process of involvement, the sense

of creative questioning about life."

He

has toured extensively with clown Bob Berky, who has helped Moschen

find his own kind of humor in his work, and with Fred Garbo. In 1985

he and Berky appeared at BAM as "The Alchemedians." He has

also performed in Bill Irwin's "Not Quite/New York" and

"The Courtroom," and in the films "Hair,"

"Annie," and "Labyrinth," where he served as

David Bowie's hands. He has also been featured on the avantgarde

performance series on television, "Alive from Off Center."

He's toured all over the world, in South America, Australia, Hong

Kong, Saudi Arabia as well as Europe. "Being able to travel is

beautiful," he says. "If you're open to people, it'll

change your work."

He

used to teach extensively, but no longer. "I always found that

the innocence of people who didn't know how to juggle was

beautiful," he says. "I could control the environment

enough not to squash their creativity and vulnerability, and to

encourage them to make mistakes, because that opens you up. Then

you'll learn about what control is. But the people

"I

had a terrible experience at the Movement Theater Festival in

Philadelphia [two years ago]. The advanced class literally started

strangling each other, tripping each other, sabotaging each other and

me, because they couldn't face the fact that they couldn't control one

ball and their body. I wasn't trying to shame anybody, I was trying to

see how they could find another basis to start from, for understanding

what a juggler

is for themselves. And then a number of people tried to steal my

material - I performed down there with Bob Berky. It just became an

untenable situation, and I ended it in a very dramatic fashion. I was

just pushed too far."

Other

instances, too, of people

copying his material or taking credit

for discoveries that he has taught them have been further

reason for disaffection. "To take the simplest, least challenging

route of taking somebody else's work

instead of developing your own doesn't make any sense. Life has

to be about risks," he declares

with some vehemence. "Art is about a certain kind of truth. And

in circumstances when people have stolen my material, either students

or whatever, the deepest anger that

I've had is that it's a violation of a kind of

truth."

Moschen's

daily rehearsal schedule changes all the time according to the needs

of the moment. Some days he might rehearse less because he's doing

other kinds of research, in books, a sculpture studio or

art galleries, or working with collaborators, to

whom he attaches great importance. He uses a

fast warm-up or a slow warm-up depending on the circumstances,

getting the circulation going and doing stretches. For relaxation, he

still likes to play golf and to work with his hands.

Asked

for advice to young jugglers, he says, "For chronologically young

jugglers, I would say work as hard as you can at what

you love, and try to know your limitations, because

then you have the possibility of extending them. For [adults]

who are new to juggling, try to learn about the history of juggling,

and use your brain." He feels it's useful to rehearse with a

mirror, looking back and forth from what

you are doing to what the objects are doing.

He

continues, "Combine as quickly as possible rather than learning

isolated tricks. That's the way to discipline yourself to have

the possibilities of making an act." He stresses "the

process of learning about yourself while you're learning the skills.

There are plateaus |

|