|

Page 30 Winter 1991 - 92

|

It

is quite natural to add clubs to a line. For each club you add, add

one spin to someone's throw. Ten is usually done with the back person

throwing long doubles. For eleven, have the front person throw doubles

too. With twelve, the dropbacks should have an added spin and maybe

the long throw can be a triple to provide yet more time. The person(s)

throwing doubles or triples should start with the extra cIub(s).

The

Box The

box makes an impressive juggling feat possible without much work. In

this formation, two pairs of jugglers are passing independently except

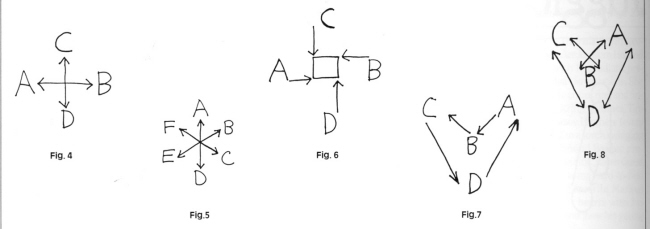

for the fact that their passes cross. Figure 4 shows a box in which

jugglers A and B are exchanging passes and jugglers C and D are doing

the same.

To

avoid collisions, we just make sure that the two pairs of passers

either (a) pass alternately so that pairs of clubs take turns going

through the middle or (b) pass at exactly the same time. These are the

alternating box and the simultaneous box. We'll assume that each pair

of jugglers is passing six clubs, but similar boxes can also be

executed with each pair passing seven or more clubs (at last summer's

St. Louis festival, an 18club box

was demonstrated in the club passing workshop by Doubble Troubble and

Happenstance).

The

Alternating Box The

easiest rhythm for the alternating box has each pair passing a

4-count, but the pairs are out of phase so that when one is passing,

the other is doing a right hand self. This is very easy, but still the

two pairs have to keep juggling at the same speed or one will

eventually catch up with the other. To start this box, simply use the

rule above: the second pair should pass when the first pair is doing a

right hand self.

A

slightly harder alternating box has each pair passing a 2-count, but

when one pair is passing, the other is doing a left self. There is

less room for error here, but it is still not terribly hard. One way

to start is to have the second pair start with two clubs in the left

hand and begin with a left self when the first pair is passing.

A

very hard alternating "box" is a pattern called entropy,

which has three evenly spaced pairs (instead of two) passing through a

common midpoint, each pair passing a 2-count (see Fig. 5). Here the

pairs are out of phase by 2/3 of a count and the timing has to be very

precise. Keep your throws somewhat inside to get through the middle as

easily as possible. It takes six experienced passers with very good

rhythm to pull this off successfully. One way to start entropy is to

have one person in each of the

second and third pairs start with four clubs (jugglers B and C in Fig.

5) so that only those two people have to time their starts carefully.

Another

possibility with six people is to have each pair passing in a 3-ct,

with successive pairs out of phase by one count (as in the four-person

2-count alternating box above). Again, keep the passes inside in these

alternating boxes. The

Simultaneous Box The

simultaneous box has everyone in the box pattern passing at once. Can

this possibly work? Yes! It does require precise timing. If you try

this with four people who have never passed together before, it'll

likely take a while before you all agree on a common speed - and it

may never happen. Each of you will need to be prepared to adjust your

speed. .

To

avoid collisions, keep your passes outside in any simultaneous box.

That means not only throwing to a point well outside your partner's

shoulder, but throwing from a point about a foot outside your leg.

To

keep everybody throwing at the same time on each pass, try the

following useful trick. Each of you should watch the person on your

right and throw at exactly the same time that person does. It's not

hard to see that person while you continue passing with your partner,

and it definitely helps keep the group's passes locked together in

time. Make

sure that you all start at the same time.

You

might find that a slow start helps you to do that. Try also to keep

the passing speed slow, since it's generally easier to stay together

at a slower speed because it allows

for correcting slight errors better than a fast passing speed does.

Now,

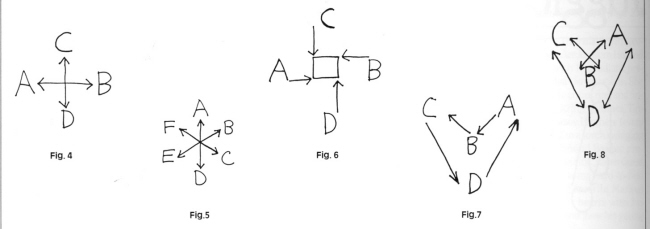

the reason that the simultaneous box works at all is that the clubs

don't all go through the same point. In fact, with perfect timing,

they simultaneously reach the four comers of a little square, about

two to three feet on a side, in the middle of the box (see Fig. 6).

Then each club travels along one side of the little square, getting

out of the way of the club behind it while the

club in front gets out of its way. If all the clubs

reach the comers of the square at the same time,

and if the square is big enough, then no collisions will

occur. Making the throws wide (at the throw and at the catch) makes

the little square bigger, and thus allows a bigger margin of error. |

|