|

|

Page 35 Winter 1993-94

|

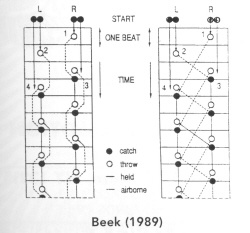

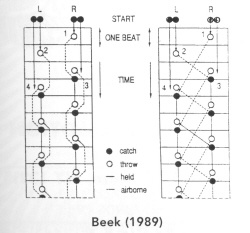

The

diagram also appeared in Peter Jan Beek's 1989 Ph.D. thesis from

Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, "Juggling Dynamics."

Beek calls the diagram a "tonality ladder," and says

he heard about it from Charlie Dancey, a former partner of the

noted U.K. juggler Haggis. The diagram also shows up in Kaskade

number 25, March 1992, in ''Juggling on Paper" by Joachim

Voigt, pp. 16-17 (note this is the same title as Simpson's

article). Voigts version has an extension for marking the type

of throw in club juggling (e.g., number of spins). The diagram

reappears in Kaskade #29, in "Workshop - Juggling Theory,

part 1: The DAB Theorum (sic) and other serious illnesses"

March, 1993, pp. 35-37, by JOTA (Jongliertheoretische

Arbeitgemeinschaft). It is also mentioned (though not used) in

Martin Probert's 1990 book, "491 Patterns for the Solo

Juggler."

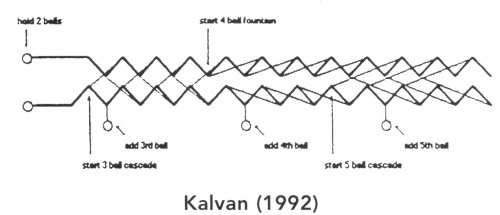

Another

variant of the diagram, designed to show the length of time that

hands spend full and empty, is in "Juggling Made

Complicated" by Jack Kalvan. Jack's unpublished paper has

many interesting results in it, including a calculation of the

maximum permitted errors to avoid collisions in standard

juggling patterns. Jack also worked on the now-defunct juggling

robot project at IBM, and is half of the noted juggling duo

Clockwork. (Although Jack and Rick Rubenstein didn't know it

when they named themselves Clockwork, the name is reminiscent of

how the Elgins, a

Vaudeville juggling group, were named. Elgin was the name of a

watch manufacturer at the time. The group walked by a jewelry

store that posted the ad, "Elgin: precision timing"

and decided that was a good name for a juggling troupe).

So,

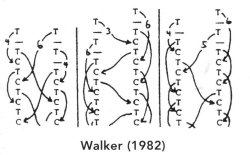

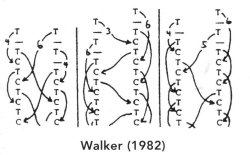

did Simpson 1986 invent the diagram? No. Both Voigt and Probert

refer back to Jeff Walker. This is the 1982 article I skipped

over above. It is "Variations for Numbers

Jugglers," in the January 1982

issue of Juggler's World, page 11. This short article, less

than one page, not only has the juggling diagram, but uses it to

invent some site swap moves, contains the basic site swap idea of

having, for example, a 5 denote a five ball cascade throw, and

even has

So

Walker laid the groundwork for site swaps and MHN, but did he also

invent the diagram? Perhaps, but around 1981 Claude Shannon began

writing an article called, "Scientific Aspects of

Juggling." It was supposed to appear in Scientific American,

but he never finished it. After gathering dust for over a decade,

it was finally published a few months ago in the book:

"Claude Elwood Shannon Collected Papers," edited by

N.J.A. Sloane and A. D. Wyner, New York: IEEE press, pp. 850864.

The paper has no site swaps, but there in Figure 5 are three

juggling patterns, depicted using the same diagram.

Interestingly,

in every place the diagram appears except in Shannon's and

Kalvan's articles, the diagram is drawn vertically with the time

axis running from top to bottom. Only Claude and Jack followed the

Apparently,

something clicked in the 1980's, causing the site swap diagram and

notation to be independently rediscovered many times. In contrast,

the 1990's are fast becoming the decade where the theory goes into

practice, with jugglers everywhere learning how to perform site

swaps. Remember when a 3-3-10 was a club passing pattern and not

an illegal site swap for 5-1/3 balls?

"The

Academic Juggler" is an occasional feature of Jugglers

World, and is devoted to all kinds of formal

analyses of juggling. Anybody who has suggestions, comments, or

potential contributions for this feature is encouraged

to write to me, Arthur Lewbel, Lexington, MA. Please

include a phone number if |

|

|

|