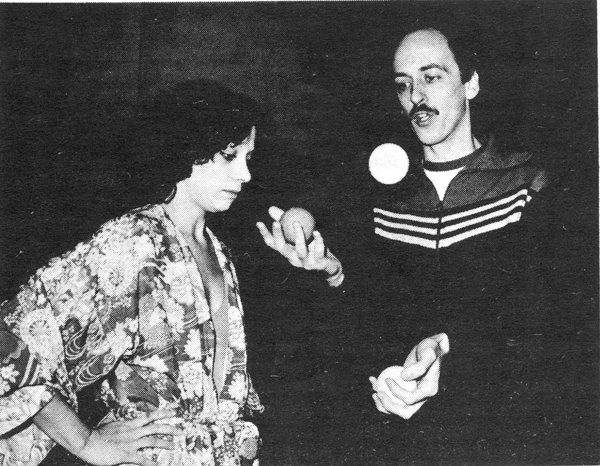

Craig Turner instructs an aspiring actress at the U. of Washington. |

Page 3 May 1980

|

By

Craig Tumer Seattle, WA Teaching

juggling to actors and performers can be a satisfying and challenging

task. As a specialist in movement training at the University of

Washington's Professional Actor Training Program, I have found

juggling to be a valuable addition to my class sequence. Aside from

all the new things it can teach an actor about his or her body, most

performers find it just plain fun.

Why

do I teach juggling? It efficiently teaches hand-eye coordination,

balance, awareness of right or left hand dominance, response to

rhythmic changes and relaxed breathing. In passing routines, it is

also valuable for developing awareness and cooperation with other

performers.

One

of the most important ideas for actors to learn is the connection

between what they imagine and what we - the audience - can see.

Juggling is an excellent way to see how clear an actor's mind is. As I

am fond of pointing out, balls do not normally have a mind of their

own and will only do what you make them do. In order to improve an

incorrect throw, aside from a little practice, an actor must

understand what he or she is trying to do and have a good, clean image

of where the ball should go. That the mind leads the body, I think, is

a selling point in juggling's favor. Imagination

over matter

All

of this is an appeal to the actor to use imagination in overcoming a

physical obstacle. An actor can see the exact consequences of unsure

juggling though in other physical skills training it is not so

obvious. I encourage previsualization - seeing where the balls will go

before they leave the hands. By emphasizing the mental process

preceding the physical, it is easier for beginners to get started, and

I have been able to offer more practical encouragement.

One

thing I look for in a juggler is physical ease and relaxation. I don't

think that juggling, for an actor or any performer, is just getting

three balls up in the air any which way, tongue half out, breathing

stopped and shoulders high. If an actor is to use juggling in

performance or in warmups, it must be a way to release energy and

relax. An exercise which increases tension is hardly something that an

actor needs before a stressful performance. No

noise, now

I

use some particular techniques in testing for relaxation and

concentration of image. For instance, if I can hear the balls hitting

the hands in a regular cascade, then I know that the juggler needs to

drop the hands more just as the balls come down.

I emphasize the softness and giving way in the hand so that there is

no resistance and resulting sound. This leads to a more circular

(figure eight) hand pattern, which is easier to sustain. It also makes

the pop of the ball up into the pattern much easier, without a stop

and start, which drains energy.

Working

up the arm, I also check to see that the

At

the end of juggling study, I have two tests: one is a brief

three-to-five minute act in which the actors can juggle balls, hoops,

pins, brooms or chairs, use the bongo board, do some passing or

whatever - but as some kind of act. This might include comic patter,

the use of some kind of dramatic situation in which juggling appears,

or, in the case of advanced jugglers, a straightforward sequence of

juggling effects. Creative

entertainment

This

is the creative test where I look for the actor's ability to get

past the technique and attempt to entertain the class. I have had good

actors who have been able to entertain us in spite of the fact that,

technically, their juggling was really not that strong. But that's

okay - I'm training actors who can do a little juggling, not the other

way 'round. The

other half of the test is called the compulsories - rather like the

school figures in skating at the Olympics. The actor is asked to start

a cascade and continue while I give instructions such as, "Make

the smallest cascade you can," "Make the biggest you

can," "Make the wildest," etc.

I

also test the actors' concentration by asking them to continue

juggling and look at me, read some words out of an ad in a newspaper I

hold up beyond the cascade, or to continue the cascade while I move in

close and place my hands under, to the side, and over the balls.

I

can tell if the concentration is off when the whole pattern begins to

veer either toward or away from my hands. If an actor can juggle with

this kind of pressure, I know he or she can do it for an audience.

I

look for devices that continue to appeal to an actor's imagination. I

had an actress recently who had trouble getting beyond three passes

until she began to say "Ah" on each throw.

Why

did this help? Vocalizing releases tension through breath and relaxes

the body. h also establishes a consistent rhythm; this is why I often

play music during juggling classes and encourage the actors to use a

variety of rhythms when they practice. This is a fundamental training

for an actor who must learn to play different characters, each one

of whom has a different rhythm.

I

think that, ultimately, juggling teaches the actor to extend him or

herself and learn to handle complicated extraneous activity without

tension or frustration. The actors need to learn to at least look at

peace while juggling. What I look for in actors, actors who juggle and

jugglers, is the ability to go beyond just "getting three balls in

the air."

Five-baller

reacts to everyday

drops By

Brad Heffler Washington, DC During

my past two years of relatively serious juggling, I have often wondered

what separates the advanced juggler from the rest of the population. I am

not referring to the actual ability to keep a multitude of balls dancing

in the air, but rather to the subtle differences in a juggler's day.

I

think I noticed the difference first right after perfecting my five-ball

cascade. It's obvious that better reflexes and quicker reaction time

characterize the serious juggler. But, until you read this, you might not

notice that, for those quicker folks, almost nothing hits the ground

around them. I'm not talking about juggling props, but about everyday

items.

When

an object is dropped, it almost seems to freeze in the air while you grab

it before it hits the ground. I

remember several examples last week to illustrate my point. A bar of soap

slipped out of my hand, only to be caught by my other hand after falling

about one foot. My roomate knocked an empty glass off the table, which I

barely grabbed six inches from the floor.

I'm sure that after reading this, you will begin to notice similar incidents in your day. So, the next time you spot someone at the next table grab a falling fork out of the air, go ask him how his fiveball cascade is coming. |

Craig Turner instructs an aspiring actress at the U. of Washington. |