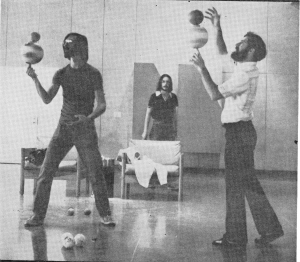

As Chris Kearney watches, MIT jugglers Arthur Lewbel (l) and Andy Rubel spin balls on balls. (Bri Serog photo) |

Page 18 December 1982

|

MIT

jugglers

claim history, technology By Arthur Lewbel Boston, MA

In

April of 1976, a half-dozen jugglers who were attending MIT

Unicycle Club meetings decided to

separate and form the MIT Juggling Club. We continued to meet at the

same time and place as the uni's did, Sunday afternoon in front of the

MIT Student Center.

Over

six years later, we still meet at the same time and place as long as

the weather is nice enough to suit our persnickety jugglers (not too

hot, cold, sunny, rainy, or windy). Otherwise, we meet in the lobby of

MIT's building 13.

This

club was not the origin of juggling at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, however. Earlier, MIT's Artificial Intelligence

Laboratory studied jugglers and juggling from the point of view of

how people learn a skill. One student, Howard Austin, wrote his entire

thesis on the subject. In part, he analyzed how jugglers build up

sequences of reflexes in their hands, that are called on by the brain,

much as a computer program receives information from the outside, and

processes it by calling on prearranged subprograms.

Juggling

at MIT often seems to get technical. Although the majority of our

members are not associated with the school, the spirit of the place sometimes

creeps in. For example, David leDoux, a past president, created decks

of computer punch cards whose holes would appear to move in juggling

patterns when you thumbed through the deck. Professor Halold Edgerton,

inventor of the strobe light, has taken pictures of club swingers and

jugglers under his lab's powerful strobes. The juggler featured in a

recent book of Edgerton's photos is Skip King, a former MIT Juggling

Club member.

Mathematics

professor Claude Shannon, who recently appeared in JUGGLERS WORLD

magazine, is from MIT. In addition to building juggling machines, he has

done original research into the mathematics of juggling.

He

notes, for example, that the geometry of standard juggling patterns are

invariant under affine transformations, although the ability to stretch

or distort patterns in this way is limited by physical conditions, such

as necessary minimal relationships between the time objects spend in the

air and the time spent in the hand. Moving away from toss juggling, MIT

has produced machines that can balance a pole, and students here built

what was once the world's largest yoyo.

All

of this activity has little to do with the MIT Juggling Club, however.

The club is just a center for jugglers in the Boston area to meet,

practice, trade ideas, and talk to each other, away from Harvard Square

and the street scene.

We

have no dues, one functional officer, and require no affiliation with

MIT for membership. In fact, we don't even have a membership list. By

always meeting at the same time and place, the club is available to any

juggler with a Sunday afternoon to spare.

The

meetings have a small core of avid regular attendees, and a hoard of

every-nowand-then'ers. Attendance varies greatly from week to week.

The range of ability in our members is also large. A few local

performers, such as Rawd Holbrook of the Fantasy Jugglers, AI Jacobs,

Michael Kass, Judy Gaiten, Dario Pittore show up most weeks. Some of our

nonperformers are also very good, including some

At

our meetings, we of course juggle and talk about juggling. Club passing

is popular here. Fads, from counting three ball variations to fire

eating, have come and gone, though year after year the club remains

essentially unchanged.

How

did all this come about? For me, it began in the spring of 1973 when,

after two years of juggling on my own, I met John Grimaldi. He told me

about the IJA, and about his juggling workshop at Trinity Church in

Manhattan. When I came to

MIT, I joined the unicycle club, and began

bringing my juggling props to meetings. Some of the other

unicyclists learned to juggle, and other jugglers seemed to drift in

from nowhere. We soon started our own juggling club, modeled on John's

New York workshop.

I

was elected the first president, and David Mark

(Spiderman the Juggler) was vice president. Among other things,

David ran the first and only MIT juggling and unicycle club show.

Back

then, club members were almost entirely MIT students. As we became more

established, the club started attracting outsiders.

We

ran a few New England Juggling get-togethers which, thanks to the

publicity available through the IJA, attracted large crowds.

The

press has also been helpful. Pictures or articles about the MIT Club

have appeared in most of the local papers, including' 'The Boston

Globe," "The Boston Phoenix," and the nowdefunct

"Real Paper." "Fortune" magazine did a story on

juggling that featured photos of the MIT club. "The New York

Times" wrote an article specifically on the MIT Juggling Club,

including photos. The article was syndicated, resulting in phone calls

from friends in obscure places who read about the club in their local

papers.

Overall,

the MIT Juggling Club has had an easy and enjoyable life. Despite

evictions and broken windows, we've kept juggling. If you're ever

passing through the Boston area, please drop in (puns intended!). For

further information, call me. Our club has been going for a long

time, and it won't be dropped any time soon. |

As Chris Kearney watches, MIT jugglers Arthur Lewbel (l) and Andy Rubel spin balls on balls. (Bri Serog photo) |