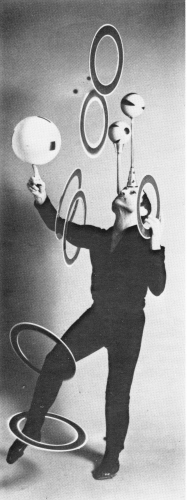

Francis Brunn's finish trick. |

Page 9 Spring 1986

|

Ageless

intensity and devotion After

almost 50 years, Brunn still looks forward

rather than back

Francis

Brunn looks forward to the 50th year of his show business career

with the same ar

Sidelined

from his performances at the Lido in Paris for several weeks last

fall by a pulled muscle in his leg, he released the energy he

normally expends in the show in a Juggler's World interview.

The tone of his speech revealed both satisfaction with his 47 years

as a professional juggler and a desire to accomplish still more with

his artistry.

Brunn's

career demonstrates artistic maturity at its finest. His act has

changed over the years in accordance with his instincts and

capability. He still attacks his work with enthusiasm and care.

Working

with his sister Lotte from 1939 to 1948 in Europe and with the

Ringling circus in America until 1951, he dazzled audiences with

speed and up to 10 rings in performance. But in the late 1950's he

felt a strong pull in a different direction. He went night after

night to watch the performance of a flamenco dancer named Antonio,

admiring the power of his carefully controlled motion and poses.

He

began changing his own act, but as he recalls it, the transition was

frightening. "My new opening was just standing in the

spotlight. I almost started shaking because I wasn't doing anything,

I wasn't moving. It was very hard to go from doing all these crazy

things to doing nothing, but once I got a feel for it I found it was

more interesting to the audience.

"Previously

in the first two or three minutes of my act I did lots of things and

the audience knew then I could do anything, but it wasn't

interesting to them after that."

He

found the challenge of learning a higher degree of control extremely

stimulating. "One of my new moves was to bounce one ball on my

head, but I did it in such a way that the audience saw the ball move

but not my body. I worked for absolute control over it like I was

inside the ball."

His

act today is designed to mesmerize an audience. "For me silence

is success," he said. "If someone comes backstage and says I

had a good audience I know I did not do well, but if they .say it was

a bad audience I know I've done well. When they don't react at the

moment I know I've made a lasting impression.

"There

is one trick where I am spinning a ball on a finger of my right hand

and holding another on the back of my neck. I roll it down my back and

kick it with my heel over my head to a dead-on balance on the spinning

ball. When I hit it perfectly it's deadly to the audience. They're

speechless. "

Time

and wear-and-tear have taken a toll on this intense artist. "The

injuries have slowed me down," he admitted. Then with a laugh he

added, "Nothing else could have!"

But

rather than retreating to perform simpler material, he has responded

with greater precision in his movement. "I don't think of adding

tricks anymore, but of eliminating things and doing more with what I

already know."

The

serious face he shows audiences is reflected in °his devotion to a

strict training regimen. He

rehearses 90 minutes each afternoon, then 45 minutes again about 90

minutes before each show. During the remaining time before his number,

he puts on makeup and stretches. He has had several operations to

repair injuries, but always resumed practice sessions as quickly as

possible. "Four days after a hip operation in 1976 I started

working on balancing one ball on another on a mouthstick as I sat up

in the hospital bed," he recalls.

Another

bad time was the death of his father in 1980. It put him in a deep

depression and prompted him to think about retirement. "But I

didn't know what else to do, I have no other interests," he said.

"I

know every act and every manager in the business, so I could be a

manager but that would be horrible! I could open a juggling school but

I would be a horrible teacher, too! So, I kept working." |

Francis Brunn's finish trick. |