In

1984 while he was at the Hacienda, the IJA held its festival in Las

Vegas, and it provided the beginning of his long association with

world records and championships. He won the festival's U.S. National

championship, and earlier that same day juggled five clubs for 21:05

to win the numbers championship in a time that surpassed the old

Guinness record set by Sergei Ignatov.

Lucas

counts it is one of his proudest moments because his father was in the

crowd to witness the feat. "That's when I had earned his respect

as a juggler - on his terms," Lucas said.

Since

that time he has set world records and has appeared several times in

noted publications for his achievements with high numbers of objects.

He reveled in his records at one time, but has become more sanguine

about their temporal nature and the feuds they tend to provoke as time

has passed. He is honored to represent the best that juggling has to

offer, but recognizes that records will all be broken, and that he can

never do more than set the bar higher for a moment in time.

"I

don't practice just to set another record or beat someone," he

said. "I do it to improve my ability within my profession, much

like an artist whose skills are ever-evolving. I suppose that it's

only human nature to make comparisons, but in the final analysis

that's an issue best left to the public and historians. As far as I'm

concerned, my goal has always been to be a good professional and to

expand the boundaries of juggling to bring honor to the efforts and

legacy of the great champions who came before."

He

worked at the Hacienda's "Fire & Ice" show until late

1986, when he was injured in a performance and had to take time off to

heal. That led to a decade-long business relationship with Anheuser

Busch that has seen him perform and direct Busch shows in Williamsburg

and Tampa. The relationship has allowed him a flexible schedule that

he has used to good advantage. He began a series of successful

speaking engagements, which included an invitation from noted author

Michael Crighton to deliver the keynote speech at the Aspen Design

Conference. He received the only standing ovation of the entire

conference, and Crighton later labeled him "a progenitive

juggling artist."

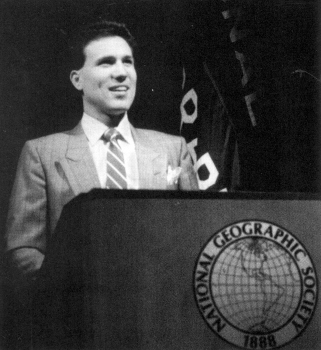

Lucas

was also the first juggler ever invited to speak at the National

Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., where he gave a lecture on the

4,000-year history of juggling, as well as an exhibition.

Another

defining moment in his career came at age 16 during his stint with the

Ice Capades. Lucas explained, "I began wondering then if this

would be my life - getting up every morning and going to tutoring,

then going to publicity calls, practice and the show in the evening. I

asked my dad when he thought I would start enjoying it all.

"He

told me then I didn't have anything left to prove, that I could quit

practicing right then if I wanted because I was already good enough to

keep getting hired. Then he talked about how juggling is an art, and

unlike a business career it doesn't promise a pension or stock

options. All we carry home at the end of the day is the pride of

performance, that we as variety artists successfully entertained an

audience."

"At

that point I had to decide whether I was in it for the money, to just

hang on until something else came along, or whether I really wanted to

keep juggling because deep inside that's what I wanted to do. I knew

then it was my destiny to control, that no one was making me practice

at that point. And since then I've juggled because I love juggling. My

father taught me how to juggle, but I learned to love it on my

own."

Because

he loves it, he has learned to adapt his classical act to the modem

entertainment medium, which seldom gives it the respect that earlier

eras afforded its artistes.

"Things

are completely different for

performers these days," said Lucas. "When I did an

intermission show for the Denver Avalanche hockey game recently, they

told me the Zamboni was broken and I had to skate around in a certain

pattern to stay out of its way. Then they asked me to cut my act from

six minutes to four right there on the spot. Jugglers of a former era

would never have had to put up with that,"

Lucas continued, "But I went out and did what they wanted, and

felt like I represented my profession well. It was the first time a

juggler had ever performed at an NHL playoff game, and when I finished

the vice president of the NHL came out and said I was the type of act

they wanted in the NHL. The important thing is that all of us can act

as good professionals and good representatives of our art, and in

.that sense contribute to it just like Bobby May and Trixie and other

greats have done."

He

tries to take a long-term view of the art, and look at himself as

another carrier of the water from past to future. His knowledge of

juggling and sports history is encyclopedic, and he feels fortunate

that his association with juggling has allowed him to meet dozens of

world-class athletes and entertainment stars.

He

has appeared twice in the past few years as the only non-Olympian in a

European all-star ice show. During that tour he had the pleasure of

teaching Katarina Witt how to juggle and

became her morning jogging partner.

Having

spent so much time around that caliber of athlete, he knows they earn

their accolades honestly through sweat and commitment. He loves and

respects that work ethic, and won't tolerate anything less for himself

in his chosen field. Since the beginning of the year he has been

living in central Florida working at Busch Gardens, performing on

weekends at NBA and NHL games.

What

the rubberneckers at Busch Gardens don't see is the several hours a

day when Lucas is alone in a nearby gym trying to stretch the limits

of his ability - because he loves that, too. "Watching me try to

throw and catch 12 beanbags is pretty boring to everyone on the

outside, but for me the time flies."

He

was working this summer toward the IJA festival numbers competition,

hoping to demonstrate a 12 ring flash and a qualifying run with 10

rings, as well as eight plates. He also hopes to open doors for his

art that future jugglers will pass through without ever knowing they

were once closed. He wants juggling to achieve the prestige enjoyed by

main-stream entertainment activities, and acts on that dream. He

sponsored the IJA Championships Trophy so that winners of the top

competition would have as beautiful a trophy to raise as winners in

any sport. He has sought the same corporate sponsorship that other

athletes enjoy. And he has broadened juggling's scope through his

training as a joggler.

He

chases his personal potential around the track daily, training at

joggling because his times are still improving and he wants to see how

fast he can become before age begins dictating a slower pace. He has

been an invited guest joggler at marathons in New York, Los Angeles,

Moscow and Tokyo, competed in dozens of races of shorter duration, and

holds the IJA mile relay record, and second best-ever times in the IJA

100 meter and 400 meter races.

Because

he trains seriously, he has been pleased to find that serious athletes

outside the world of juggling take him seriously. Many international

track stars preparing for this summer's Olympics were training at the

University of South Florida where Lucas also trains, and most are

shocked at their first exposure to his seemingly irreverent angle on

their honored tradition. But when they come back day after day and

find him there again and again, sweating and straining in all

seriousness to cut tenths of seconds off of laps, they gain respect

for him as a fellow athlete.

He

has tried for several years to qualify as a joggler for the finals

in the 400 meter run at

Florida's state track championships, the Sunshine Games. But

he has never been able to break the 50 second time necessary to join

that elite field. But because of his determination and persistence,

the event director invited him this year to give a joggling

exhibition of the 400 as part of the meet. "I didn't quit, and

I earned this man's respect. I'm proud of that as an athlete,"

said Lucas.

He

works hard in part because he knows jugglers of the past would do

the same if they were around today, and he intends to do his part to

keep the tradition alive.

"I

hope above all to inspire other jugglers," he said. "What

I want to say most of all is that there is no limit to what you can

achieve as a juggler, you can create anything you want. Look at what

Michael Moschen has done, or Anthony Gatto. They have approached the

art in completely different ways, but taken it to an incredible

level. But first and foremost you have to ask yourself if you're

ready to make the necessary sacrifices."

"Are

you willing to put in the hours and go through the frustrations? As

an artist, you have to be willing to start down that road without

knowing where it will take you, and with no guarantee that there is

financial reward at the end. It takes great artistic courage to come

back to the canvas day after day when you aren't always receiving

recognition for your effort. But that's the definition of

dedication. All you can hope for is that your commitment to the art

will eventually be respected, but even that might not happen in your

lifetime."